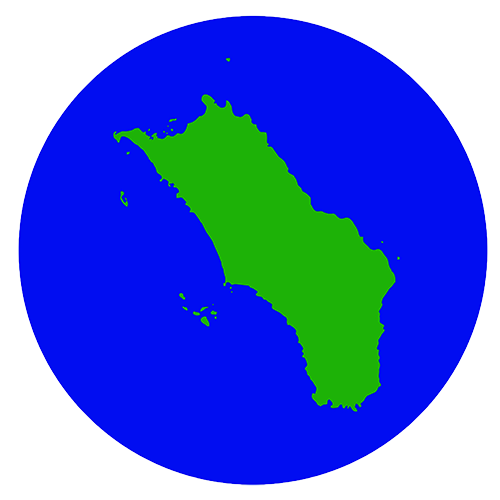

History of Nias Island

Early history and life on Nias

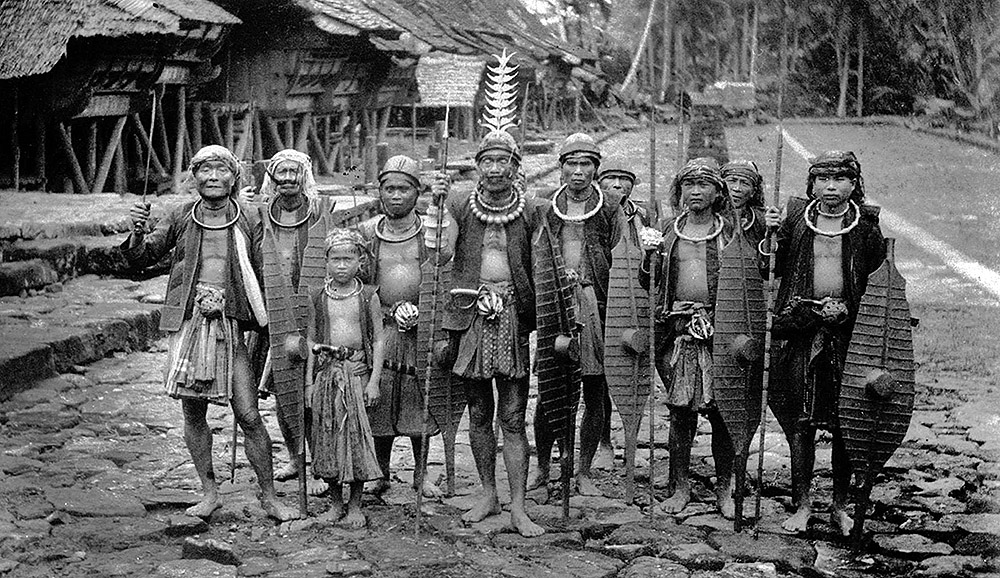

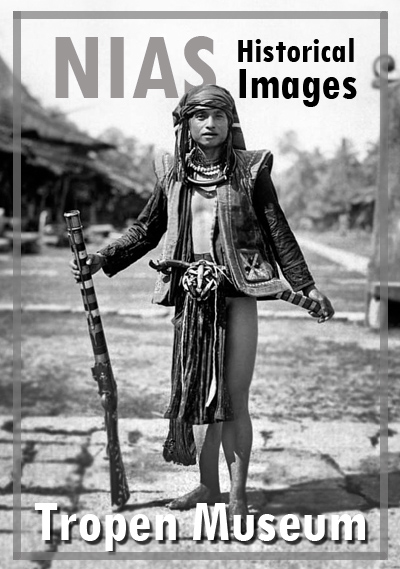

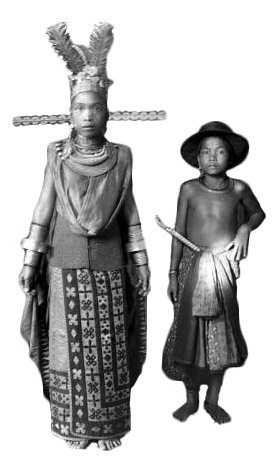

Nobleman from South Nias

Nias Island is positioned near one of the main cross roads of South East Asia and has a long history of interacting and trading with other cultures. The first written account of Nias comes from a Persian merchant who in 851 AD visited Nias Island, noticing that the local noblemen wore lots of beautiful gold jewellery and had a penchant for headhunting. Early on it was noted that Nias Island had complex social structures and some of the finest architecture, statues and weaponry in the region.

Niasans sold their produce to passing traders in exchange for precious metals and textiles. With the emergence of the slave trade in the eleventh century, peaceful trading and cultural exchanges became rare. Slave traders, mainly from Aceh, regularly raided Nias Island in search of slaves. Nias people withdrew from the coasts and build their villages in the interior on top of fortified hilltops.

When slaves became a commodity the chieftains of Nias also became involved in the trade, selling captured enemies in exchange for gold. For a long time the people of Nias lived in a state of perpetual conflict, defending themselves against slave raiders or engaging in intertribal warfare. Nias society developed a culture of war, focusing on constructing defences and making weapons. Young men were brought up to become fierce warriors and training started at an early age. As a result Nias had brilliant fighters, builders and blacksmiths but not very skilled farmers.

In between the fighting Nias warriors often practiced headhunting. This used to be a grisly but very real part of Nias culture. Heads were used for ceremonial purposes such as funerals of chieftains or the erection of a chiefs house. The act of taking a head was an important rite of passage for a young warrior. A young man needed to bring a head back to the village before being allowed to marry or sit in on the village council. The more heads a warrior had taken the higher his status in Nias society became. Successful head hunters wore distinctive neck rings and it was believed that the captured heads brought protective forces to the village. For rites of passage and warrior prestige, heads were taken in battle. But for heads to be used for ceremonies any head would do and head hunting parties often preyed on neighbouring villages or set ambushes along roads.

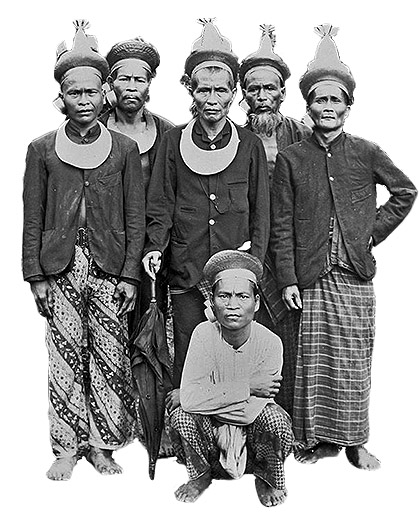

A chief with a group of warriors in South Nias.

Nias people were strictly hierarchical and divided in three classes; noble men, commoners and slaves. Each class had different levels. The chiefs were the highest of the noblemen, almost closer to gods than human. Next came the noble men who were involved in governance. The rank of a commoner was more fluid and depended on his wealth (gold, pigs and slaves) and ability to provide the sacrifices necessary for the feasts of merit (Awasa). Slaves were divided in three levels; prisoners taken in war, debtors who couldn’t pay, and criminals with a death sentence who had been redeemed by their owner. Prisoners of war were the lowest category and were sometimes sacrificed when heads were needed for ceremonies. Even though these classes don’t have any practical meaning anymore, people are still aware of the origins of each family. Descendants of noblemen still occupy high positions on Nias, while poor day labourers often are descendants of slaves.

Nias religious beliefs

Nias people believed in gods living in the worlds existing above and below earth. There were several levels in both the upper and the lower world where different gods resided. The first god came out of chaos to create the world. There were different names for this first creator god in different parts of Nias. Nias people saw themselves as the “pigs of the gods” with whom the gods could do as they pleased. They could feed them and treat them well or kill them, depending on their mood. Sickness and disasters happened when gods from the underworld ate the shadows of people on earth. Regular sacrifices of pigs were made to satisfy the gods. In the level closest to earth there was a village from where the ancestors of Nias people eventually came down to earth, somewhere in the Gomo region.

Nias people believed in gods living in the worlds existing above and below earth. There were several levels in both the upper and the lower world where different gods resided. The first god came out of chaos to create the world. There were different names for this first creator god in different parts of Nias. Nias people saw themselves as the “pigs of the gods” with whom the gods could do as they pleased. They could feed them and treat them well or kill them, depending on their mood. Sickness and disasters happened when gods from the underworld ate the shadows of people on earth. Regular sacrifices of pigs were made to satisfy the gods. In the level closest to earth there was a village from where the ancestors of Nias people eventually came down to earth, somewhere in the Gomo region.

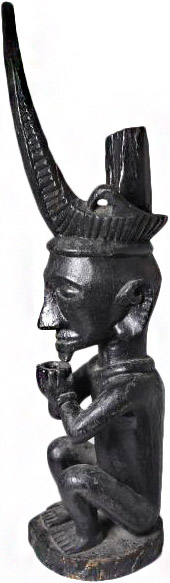

Ancestor worship was at the core of Nias beliefs and idols played important roles in each family’s life. The most important idol was the Adu Zatua statue which was imbued with the spirit of ancestors. Sacrifices to the Adu Zatua were made during important events such as births, weddings and deaths. The statues were places in the main room of the house and in some big traditional houses there were hundreds of statues filling the entire front room.

Nias religious life consisted of a complex system of rituals and sacrifices to appease ancestors, avoid evil spirits and maintain the balance between the upper and lower gods.

Colonialism

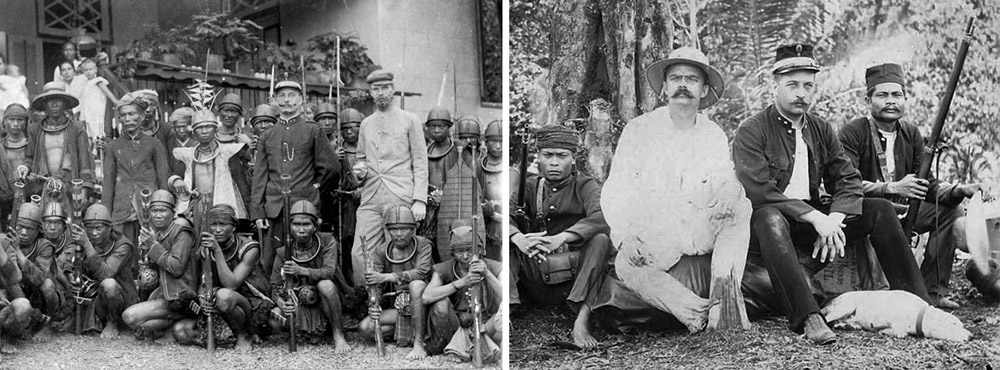

When the VOC (Dutch East India Company) arrived in Indonesia, Nias Island was known to the Dutch as source of slaves exported to Aceh and Padang. In 1669 the VOC started trading with Nias Island. Initially they traded only in produce, but as this was not profitable enough they soon got engaged in the slave trade. Slaves from Nias were bought by the Dutch to be used on farms owned by the VOC in Sumatra. In 1693 the VOC established its first base on Nias, in Gunung sitoli, where they built a harbour and store houses.

In 1740 the VOC left Nias for good as the companies influence in Southeast Asia was veining. 1776 the English arrived and took over the trading post at Gunungsitoli but soon abandoned it as it was not profitable enough. Eventually the Dutch assumed control of the island again in 1825. Their control only reached the immediate area around Gunungsitoli and there were many uprisings and revolts against the Dutch, particularly in the south. A Dutch mapping party was attacked in Lagundri in 1846 and the Dutch retaliated by burning down the whole village which at that time had many traditional houses. In 1855 the Dutch intervened in a conflict between two villages and sent thousands of soldiers to attack Orahili village in the south. Incredibly enough warriors from Orahili fought off and defeated the Dutch force. There was an uneasy calm for six years until locals became provoked by an unpopular Dutch commander and attacked the fort in Lagundri, inflicting great losses on the Dutch. As a punishment the Dutch sent an expeditionary force of six hundred soldiers. Whole villages were burned to the ground including many of the great Omo Zebua buildings. Fed up with this constant conflict the Dutch more or less withdrew from Nias for over 30 years. Most Nias people continued to live a traditional lifestyle despite the Dutch presence in a few fortified places around the island. But in 1900 the Dutch sent a large army contingent to Nias to finally secure the areas outside of Gunung Sitoli. Full control of the whole island was only established in 1914, one of the last areas to be ‘pacified’ by the Dutch in all of Indonesia.

Dutch Colonials on Nias Island. The main settlement was Gunungsitoli, but there was also military forts and missions in other places.

One of the lasting impacts of Dutch colonialism was the breaking up of the traditional village structure. Traditionally Nias villages where built on hilltops for defensive purposes. The Dutch constructed a road network on the island and decreed that local people had to live next to these roads. This had two purposes; goods from outlying districts could effectively be transported back to the capital of Gunungsitoli and Dutch soldiers could easily reach villages in case of rebellions.

Christianity

The first protestant missionary, E.L. Denninger arrived in Nias in 1865. He is widely credited with establishing Christianity on Nias. The first 30 years saw very slow progress, as it was almost impossible to travel safely out of Gunungsitoli. After the Dutch established full control of the island in 1914, Protestant Christianity spread rapidly across the island, and particularly so in the North. During the initial religious fervour many traditional practices were banned. Quite understandable headhunting and slavery was forbidden. The raising of megaliths and carving of wooden statues was considered idolatry and was also banned. As the new religion spread it was soon co-opted by indigenous leaders. Missionaries may have brought Christianity to Nias but the Christian movement was led by local preachers and leaders.

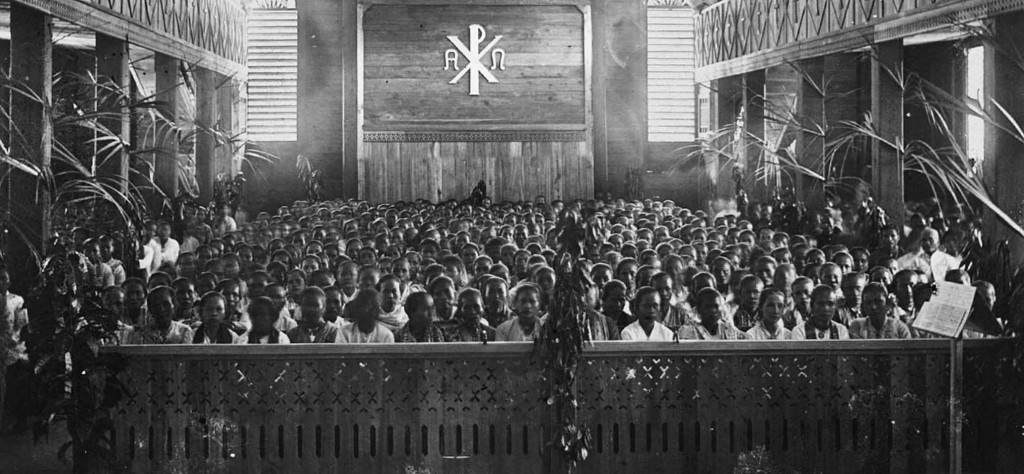

Christian service in Rijnsche Zending church in Gunungsitoli. 1920’s.

Religion still plays an important role on Nias. Priest and church leaders are important figures in the community and many official functions takes place in churches and starts with a prayer. Social and political life are closely intertwined with religion which can be clearly seen on Sundays when most people dress up in their finest and attend church. Today there are many different Christian denominations on Nias including Catholic and Evangelical churches. There is a Muslim minority (6%) which is a mix of Niasan converts and immigrants from Aceh. They are concentrated along the coast, in particular the larger towns.

Modern History of Nias

World War II

Japanese bunker at Toyolawa beach

During World War II Japan occupied Indonesia, known then as the Dutch East Indies. The Dutch capitulated in April 1942 and the Japanese arrived to Nias soon after. Prior to the occupation there was a tragic incident on Nias. The Dutch had interned all Germans in Sumatra at the outbreak of war. As the Japanese approached the Dutch tried to send the prisoners (mostly missionaries and their families) to India on board the ship merchant ship “Van Imhoff”. Near South Nias it was attacked by Japanese torpedo planes. Over 400 German civilians died in this tragedy.

Initially, most Niasans welcomed the Japanese as liberators from their Dutch colonial masters. This sentiment changed as people on Nias had to endure many hardships to support the Japanese war effort. Bunkers and fortifications were built around the island in preparation for an allied invasion. Today some of these bunkers can still be seen; around Gunungsitoli and also in the north and south of Nias. Some of those installations were attacked by the British submarine HMS Terapin in 1944. When Japan surrendered in August 1945, it took several weeks before the news that the war had ended reached the island.

Independence

Independence celebrations in Jakarta 1945

Indonesian independence was declared two days after japans unconditional surrender on the 17th of August 1945. This day is known as Hari Merdeka or Independence Day in Indonesia. Due to its isolation, it took seven weeks for the news to reach Nias. Local Nias leaders immediately declared loyalty to the new Indonesian republic. As there was no Dutch on the Island at the time Nias was spared from the fighting that took place in many other places of Indonesia. During 1947 a Dutch ship bombarded Gunungsitoli, Hinakos and Telo Island, but there was no ground fighting. It would take four years of armed conflict and political negotiations before the Dutch recognized full Indonesian independence.

After Indonesian Independence, there was a period of several years with political instability as different factions struggled to control the new nation. Nias avoided conflict by staying loyal to the central powers that eventually became the rulers of modern Indonesia. During the following decades there were many social and political upheavals in Indonesia but most of them completely bypassed Nias.

Nias Island was largely ignored by the central government in Jakarta. It was the poorest and least developed regency of North Sumatra Province. No real effort was made by the central government to develop the island. The interior of the Island had very little infrastructure and many villages could only be reached by foot.

Tourism

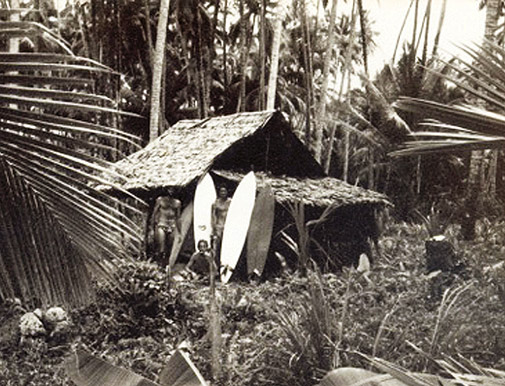

First surfers camp in Lagundri (1975).

In 1974 the Dutch cruise ship MV Prinsendam visited South Nias. The year after Australian surfers Kevin Lovett, John Giesel and Peter Troy traveled to Sorake in the south of Nias and found one of the best surf waves in the world. This was the beginning of tourism on Nias. In the 80’s Sorake Beach had become a well know surfing destination and stopover on the Southeast Asian overland trail. From late 70’s into the 90’s small cruise ships visited Nias, and passengers were taken to traditional villages in the south. But due to the remoteness of the island and lack of infrastructure it never really developed beyond being a destination for hard-core surfers.

Dutch cruise ship MV Prinsendam visiting South Nias in 1979. Photo by Alain Viaro.

As the rest of Indonesia, Nias experienced a small economic boom in the 90’s and some infrastructure projects took place on the Island. But most of the island was still very inaccessible, with few functioning roads. Development on Nias came to a standstill during the Asian financial crisis of 1998, as flights and ferries to the island were cancelled and the budding tourism industry stopped in its tracks. Nias was largely a forgotten backwater of Indonesia until two natural disasters changed the Island forever.

2004 Tsunami & 2005 Earthquake

The Boxing Day tsunami hit Nias Island on the 26th of December 2004. The west coast bore the brunt of the destruction with many fatalities, but all coastal communities were impacted. Many boats along the coast were swept away and houses were inundated by seawater. This was bad enough but only three months later a much worse disaster would be inflicted on Nias.

On the 28th of March 2005 a massive 8.7 earthquake struck just north of the Island. Many buildings collapsed resulting in more than 600 dead and thousands injured. Infrastructure across the island was severely damaged and many communities were completely cut off.

Apart from the obvious loss of life and destruction, the earthquake also changed the landscape of the Island. Due to the land uplift caused by the earthquake the whole island was tilted on its side. On the northwest corner of the island uplifts of up to 2.9 meters were recorded. This caused dramatic changes to the coastline; islands increased up to ten times in size and new islands appeared where none had been before. On the west coast the waterline was now between 100 – 300 meters further out, while on the east coast the waterline had moved inland a few meters. Some beaches disappeared completely while new ones were created elsewhere. The effects of the land uplift can clearly be seen to this day, especially on the west coast where some pre-earthquake beaches are now several hundred meters inland.

After the earthquake in 2005 parts of the coastline on Nias was uplifted, between 1-3 meters. As a result many reefs are now exposed.

Rebuilding Nias

The months after the earthquake were very difficult for the people of Nias. Every single bridge had collapsed and the ports were badly damaged. The majority of the population were completely cut off and were stuck in their villages without services and supplies. There were rumours that smaller islands like Asu had disappeared into the sea. Trade and tourism stopped, and with it the main source of income for many families. Repeated aftershocks terrified the population and many fled their homes along the coast. Many of these people ended up living in camps in the interior of the island under very primitive conditions. Others managed to trek to Gunungsitoli, and from there evacuated to the mainland.

New and old bridges across Muzoi river. The old one to the left was destroyed during the 2005 earthquake.

Due to the Boxing Day Tsunami three months earlier there was a huge international emergency operation underway in nearby Aceh province. When the impact of the earthquake in Nias became known, disaster relief organisations were already at hand to help. Emergency personal from many countries quickly travelled to Nias to provide assistance.

Red cross house in North Nias

Once the immediate rescue operations were over by the end of 2005 the reconstruction-phase began. Between 2006 and 2010 many international and Indonesian organisations put in an enormous effort to re-build Nias. This period is sometimes called the ‘NGO-era’ on Nias. Organisations like the Red Cross, UNICEF, OXFAM, ILO, AUSAID and Caritas (and many more) sent permanent staff to live and work on Nias. Apart from a few missionaries this was the first time foreigners had worked on Nias Island since the Dutch left. Funds and technical assistance flowed into Nias like never before. Working side-by-side with foreigners and other Indonesians, many previously isolated communities became exposed to the outside world. As a result Nias took a great leap forward in its development.

Nias Island today

During a nationwide drive for greater regional autonomy in Indonesia, it was decided to split the administration of Nias Island into four regencies and one municipality. The new regencies were inaugurated between 2008 and 2009. This meant that many important decisions would be made locally rather than in far off Jakarta. Being some of the youngest regencies in Indonesia meant that local governments on Nias had a very steep learning curve.

As a result of the massive rebuilding effort, the infrastructure on Nias is better today than it ever was before the earthquake. One of the most remote corners of Indonesia is now well and truly connected to the rest of the country, and it is possible to travel comfortably from Medan or Singapore to Nias is a couple of hours.

Students from North Nias, part of the PASKIBRAKA team that raises the flag during Indonesia’s Independence day

Young people now have access to better education on Nias as well as higher education on the mainland. Many people who left the island after the earthquake are now returning with education and work experiences from other parts of Indonesia, helping Nias to improve and develop. Nias is still lagging behind in many areas, but since the earthquake and the rebuilding efforts the island is now slowly catching up with the rest of Indonesia.

Learn more about the history of Nias from the Nias Heritage Museum History page

Adu Zatua - wooden ancestor figure

Adu Zatua - wooden ancestor figure Adu Zatua - wooden ancestor figure

Adu Zatua - wooden ancestor figure Adu Zatua - wooden ancestor figure

Adu Zatua - wooden ancestor figure

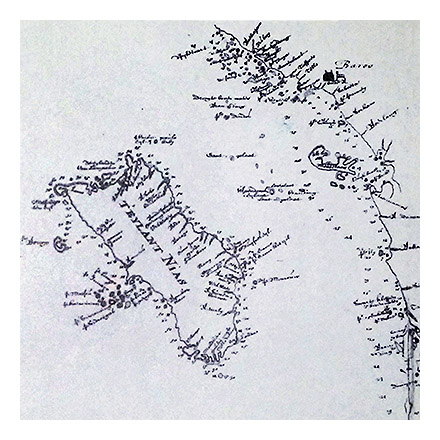

One of the first known maps of Nias by Gravehage in 1669

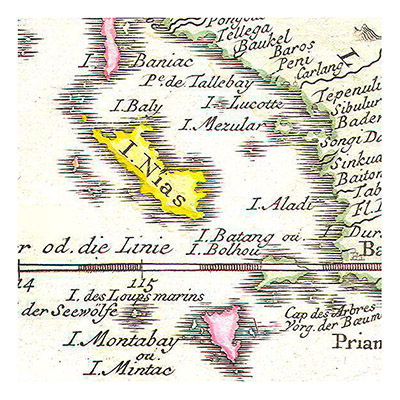

One of the first known maps of Nias by Gravehage in 1669 Another early map of Nias by Bellin in 1750

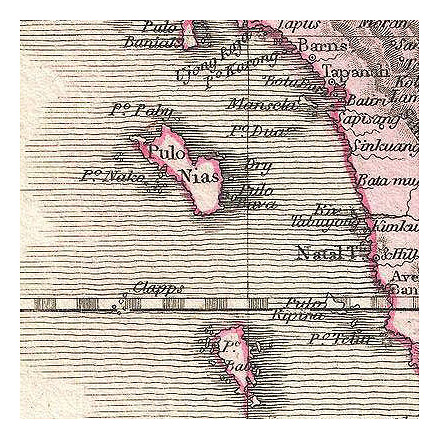

Another early map of Nias by Bellin in 1750 Map of Nias by Greenleaf in 1842

Map of Nias by Greenleaf in 1842 Nias Warrior wearing the"Kalabubu"neck ring worn by courageous fighters

Nias Warrior wearing the"Kalabubu"neck ring worn by courageous fighters Dutch colonial VOC soldier, 1600's.

Dutch colonial VOC soldier, 1600's. South Nias noble-man

South Nias noble-man South Nias warrior with blunderbuss gun

South Nias warrior with blunderbuss gun "Siulu"priestess in full regalia, South Nias

"Siulu"priestess in full regalia, South Nias Nias hunter looking for wild pigs

Nias hunter looking for wild pigs

Gunungsitoli chiefs 1910

Gunungsitoli chiefs 1910 Dutch colonial soldier, Indonesia 1930

Dutch colonial soldier, Indonesia 1930

Current traditional Nias dress worn by Gunungsitoli tourism ambassadors 2015

Current traditional Nias dress worn by Gunungsitoli tourism ambassadors 2015